At ACDI/VOCA, each of our projects includes a Collaborating, Learning, and Adapting (CLA) plan. We have processes in place to allow for reflection, learning, and adapting. CLA principles guide our internal programmatic learning, which may lead to project pivots or amplification of successes. However, one project, the USAID Resilience Learning Activity (RLA), looks at CLA in a completely different way. In fact, the team says, “CLA is our heartbeat.”

On the journey to helping communities become self-reliant, RLA takes a backseat. The project delivers its activities through a locally led facilitation approach. Its theory of change posits that if the local county governments’ and implementing partners’ capacity for learning and adaptive management are strengthened, they will make decisions informed by evidence. As local leaders, they will build systems to be more resilient to shocks and stresses.

In this way, RLA and our local partners act as a backbone support organization and facilitator for its many coordination mechanisms CLA is the vehicle RLA uses to reach its objectives (see below to learn information about RLA’s coordination mechanisms.)

“All our activities are geared towards promoting [CLA]. All our activities are efforts that are locally led, data-driven, and use CLA for collective impact.”

Mercyline Adhiambo, Deputy Chief of Party of RLA

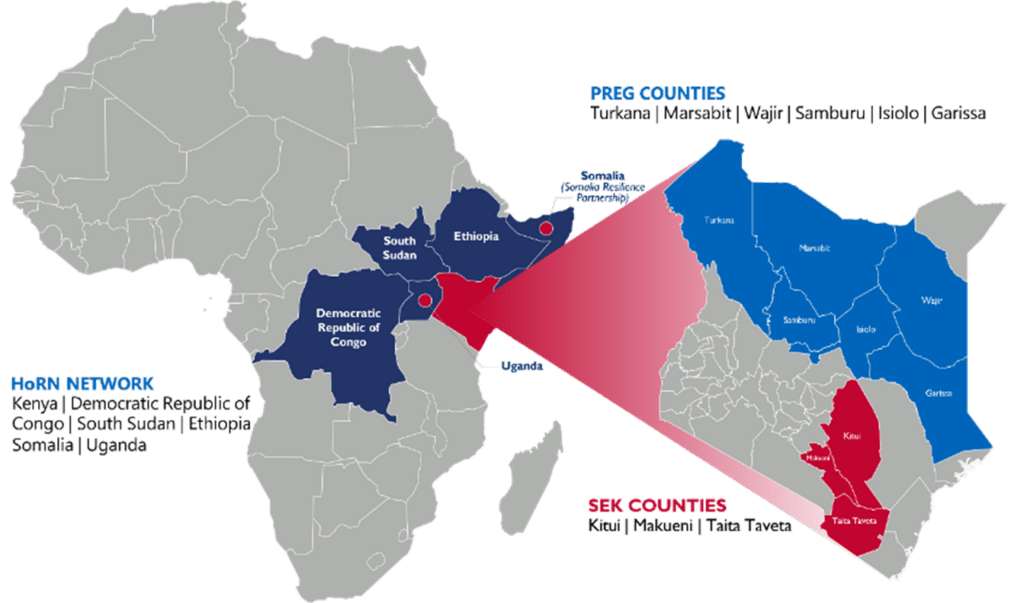

RLA operates in six countries: Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Uganda. USAID Kenya and East Africa first developed RLA to help local actors collaborate and drive inclusive economic growth and well-being. RLA’s overall objective is to support local, national, and regional stakeholders, USAID implementing partners, and the USAID Mission itself in undertaking resilience programming based on evidence that will help communities manage conflict, mitigate natural disasters, and foster economic well-being.

Step One: Joint Work Planning

One example of how RLA puts CLA into action is through joint work planning (JWP). While this may not sound particularly exciting, it is incredibly important. Before this approach was in place, county governments would budget for specific activities. At the same time, several USAID-funded programs led by different implementing partners would budget for specific activities in the same communities. This occurred without any coordination, causing overlapping efforts.

Now, JWP is a process that begins with county governments from water, health, education and other sectors. First, they come together to co-create an annual development plan and budget for the fiscal year. Then, RLA brings in various USAID implementing partners working in the same counties and sectors. These partners agree on activities that align with their own objectives and support the respective county governments. When the process is complete, the governor and USAID representative sign off on the JWP documents that provide a reference point each year on how each entity can sequence, layer and integrate (SLI) their respective program activities to maximize the benefit for each respective community.

With RLA currently entering its fifth year of operation, counties outside of its targeted areas are requesting similar support. Non-USAID-funded implementing partners have even expressed interest in being involved in the JWP process.

“In some counties that have been doing this for the last four years, RLA no longer leads the process. Local leaders in the county governments are taking the initiative. Any new USAID implementing partner is engaged by the county government, who invites them to join the [JWP] process and to co-create and co-invest. There is a lot of opportunity for this to be sustained due to the local ownership and local leadership.”

Mulinge Mukumbu, Chief of Party of RLA

Step Two: Implementation

Next, implementation begins. USAID implementing partners sit down with county government officials to agree on how to implement the activities and share the costs. For example, if the JWP outlines training community health workers, the parties would decide who is responsible for developing the modules, paying for the facility, and delivering the training. Once the activity begins, quarterly pause and reflect sessions take place to do a pulse check on how the implementation is going and co-monitor the process.

Plans in Action: How Joint Work Planning Improved Water Access

As a practical example, take Marsabit County, where a key challenge is water access due to recent drought. RLA convened partners to discuss the problem. The county government did not have the budget to complete a full project, but they were able to provide public land. The Kenya Resilient Arid Lands Partnership for Integrated Development (Kenya RAPID) agreed to revamp the water infrastructure. The USAID Nawiri program committed to providing desalination equipment and technical maintenance engineering services, including the installation of pipes and construction of steel storage tanks. A private-sector firm, Maji Milele, agreed to install a prepaid meter system for people to access water using ATM cards loaded with credit.

Through this SLI collaboration, local actors created the Bubisa Water Facility. The facility’s daily revenue grew by over 520% daily from 3,000 KES ($23) to 20,000 KES per day ($153). As demand in the county grew, local actors built more than 100 water kiosks. The ATM technology increased transparency, eliminated cartels, created 32,000 jobs for women and youth, and decreased women’s need to walk long distances to collect water.

“From the time we got involved in this kind of arrangement, we have seen that it is easy to know what the partners are doing and even for the partners to know what the county is doing because we come together and co-create, we come up with priorities, and we’re able to tell what is the county government putting in it and […] what are our partners putting in this initiative of addressing the needs of the communities.”

Lydiah Letinina – Investment and Partnership Coordinator, Samburu County

The Impact of Streamlining Our Efforts

The benefits of JWP are evident in Kenya. Over RLA’s 5-year period, a total of 37 billion KES (est $283 million) in USAID and county government co-investments have been mobilized through JWP. Thanks to better coordination, there is less duplication of efforts among the 33 USAID implementing partners and nine Kenyan county governments.

County governments have appreciated the coordination efforts and benefits of JWP; county governments have adapted the model and set up Donor Coordination Units within their leadership structures for the coordination of all donors in their respective counties, including non-USAID donors. Further, two Kenyan counties, Kitui and Samburu, have institutionalized JWP into their County Government Development Integrated Plans, ensuring the sustainability of the initiative, even as political leaders may change.

“To me, the unique thing about the partnership is the way we do the co-planning and co-investing and monitoring together. There is no project that can be said to belong to a certain institution. It’s actually owned by the community because eventually, the community is the one which generates the priorities.”

H.E. Dr. James L. Lowasa – Deputy Governor, Isiolo County

Learn More about RLA’s Coordination Mechanisms:

RLA facilitates and works through several coordination mechanisms, initially put in place by USAID.

- Southeastern Kenya (SEK): SEK brings together USAID implementing partners, county governments, and local actors to build resilience and avert a return to dependence on humanitarian assistance in three counties in southeastern Kenya.

- Partnership for Resilience and Economic Growth (PREG): PREG brings together USAID implementing partners, county governments, and local actors to build and strengthen resilience among vulnerable pastoralist communities in nine counties in Northern Kenya.

- Somalia Resilience Partnership (SRP): A similar approach to RLA’s management of PREG and SEK is being applied in Somalia, bringing together local governments and implementing partners to coordinate and align efforts. Under RLA, Mercy Corps is leading this effort in Somalia.

- HoRN Network: A coordination network that builds resilience in areas of recurrent crisis throughout the drylands of East Africa. It serves as a coordination and learning platform to end extreme hunger and promote humanitarian-development-peace (HDP) coherence through knowledge sharing to replicate and scale successful initiatives in the region.

Learn more about the Bubisa water project example.

Learn more about our current projects in Kenya.

Learn more about our history in Kenya.

Comments